Beyond Reasonable Doubt ?

October 24, 2010 2 Comments

Anyone who is interested in the virtuous administration of justice and the impartiality of such a system adheres to the concept of innocent until proven guilty.

It is one of the few weapons democracies’ have to defend the individual against the tyranny of the state and institutionalised despotism.

Those who are ‘old school’ can remember hangings, those of James Hanratty and Peter Allen, for instance. In those days the common consensus was that:

“Far better to let 9 guilty men go free than hang an innocent man”

But today both homicide and rape carry similar tariffs. For either offence a sentence of 7 years or ‘life’, ie around 15 years, is not uncommon. The meticulous thoroughnesses once reserved for capital offences, namely murders, should logically now be extended to rape. But is it ?

With the introduction of life sentences washed away the need for judicial thoroughness and the rigour demanded for judicial precision has been permanently lost. No longer did anyone’s life hang on a thread. The resulting intelletual fudge means that today Hanratty would have been convicted on far flimsier evidence than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” benchmark standard of 1963. (See Roy Burnett, who was freed in April 2000, aged 56, after serving almost 15 years for an alleged brutal rape he did not commit. See also Appendix A).

In the matter of anonymity for rape defendants politicians have long made impartiality impossible for this one crime– and deliberately so . The criterion of “beyond a reasonable doubt” has been utterly compromised and adulterated by political lobby groups to the point where it is impossible to give a man charged with rape the ‘benefit of the doubt.’

Approach any female MP from Anne Widdecombe (Cons) to Yvette Cooper (Lab) and the response is the same; they believe 101% that:

“. .. . .supporting disclosure of the defendants name encourages other female rape victims to come forward.”

So let’s have a closer look at that supposition.

The implication is that women are intimidated, or petrified, or easily deterred from reporting rape and sexual assaults to the police – or somehow in some other way made to feel nervous.

The number of rape allegations reported by the police each year is not in the hundred but in the thousands (see Fig 1). Indeed, the last time rape allegations reported to the police totalled less than a thousands was long ago in 1973 when there were 998 allegations made.

The number of rape allegations reported by the police each year is not in the hundred but in the thousands (see Fig 1). Indeed, the last time rape allegations reported to the police totalled less than a thousands was long ago in 1973 when there were 998 allegations made.

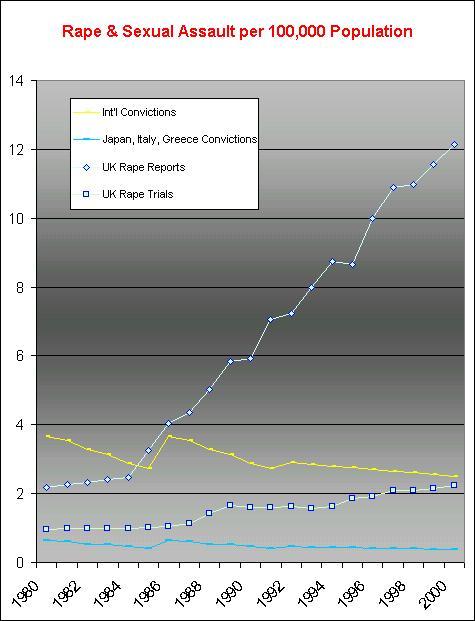

Fig 1.

In 1974 the 1,000 barrier was broken with 1,052 rape allegations being made to the police. Today, 2010 the figure is in the region of 14,000 allegations per annum.

Escalation

Why, no one ever seems to ask, did rapes take off in 1984 ? And why have they never ceased to increase ?

Why do other countries have stable or declining trend lines for reported rapes but Britan has one that climbs ever upwards ? For instance, US rape data (see Fig 2 right) continues to fall between 1973 and 2007.

For instance, US rape data (see Fig 2 right) continues to fall between 1973 and 2007.

Fig 2.

By no measure and by no stretch of the imagination can this be interpreted as women being intimidated, or petrified, or easily deterred. In fact, there are financial rewards (compensation) for making rape allegations ranging from £7,500 to £22,000 per female claimant, courtesy of the tax-payer.

From information gleaned form official statistics we can see that in 1975 there were 1,040 ‘reported’ rapes and 409 of these went to trial (Fig 3). [1] The remainder, 631, were cases where the charges were dropped or where there was a lack of evidence or an insufficiently robust amount to present to a judge.

The numbers coming to trial altered only slightly by the mid 1980s compared with the number of reported rapes the latter had doubled but the numbers coming to trail had increased by only about 100.

The numbers coming to trial altered only slightly by the mid 1980s compared with the number of reported rapes the latter had doubled but the numbers coming to trail had increased by only about 100.

The most significant change is seen in the period from the 1980s to 2003 (see Fig 3).

In this 20 year period, allegation of rape made to the police soar from 1,800 a years to 13,000 pa.

Left: Fig 3

By 2003 the level of allegations was at 13,000 pa and although ‘coming to trial’ numbers had swollen a little to 1,063, the number of ‘convictions‘ remained only slightly higher than in 1995 (578 v 710).

The very point made by anti rape anonymity lobby is precisely their undoing.

They complain that the conviction rate is only 6% – and measured this way they might have a superficial point. However, the deeper meaning to these number is that women are demonstrably ‘not afraid’ to come forward to report rapes, even if so few prove to have enough evidence to convince a jury.

Nor is it purel;y the crime of rape that is falling. As Fig 4 shows, all violent crimes in the US are falling.

Fig 4

In a letter from the Home Office (April 8th 2002), the question of anonymity was addressed in these terms; save for juvenile cases where reporting restrictions are imposed the:

“ . . . . only other major exception is that the identity of the victim (whether male or female) is protected where an allegation of rape or some other serious sexual offence is made. . . . . Not only does this protect the victim from hurtful publicity but it is designed to improve the administration of justice by encouraging them to report such crimes to ensure that rapists and other serious sex offenders do not escape prosecution.

NB. But as we have seen in reent years even juvenile cases are not spared publicity when the charge is rape of a female.

For 10 years or more this has been the standard defence and official position of the Home Office but in 2009 another Home Office they accepted that there is a 2nd victim in rape cases – those who are falsely accused.

Further on the 2002 Home Office letter states:

“However, the criminal justice system operates on the system of openness, which is considered to be a vital ingredient in maintaining integrity and public confidence, and in encouraging other victims to come forward. Restrictions on this openness have to be fully justified and can only be granted in very exceptional circumstances.”

Those restrictions seem to have become both automatic and permanent. If they do encourage other victims to come forward they appear few in number for most, the 11628, are fraudulent or marginal (13,441 less 1,813 = 11,628).

The John Warboys case (April 2009) is often cited as an example of where other women came forward. But the reality is quite different. It was the police who failed to link together the common patterns that allowed this man to commit sexual assaults on 12 women, and one rape, not 19 rapes as is sometime mentioned in reports. [2]

Justification for lop-sided anonymity is dealt with in this manner:

“Anonymity for such complainants is designed not only to protect them from hurtful publicity for their sake alone but also to encourage victims of sexual assault to report the offence and co-operate with a prosecution. These arguments clearly do not apply in the case of the accused. The equality of treatment should be between all defendants, not between the victim and the defendant.”

Under the Contempt of Court Act 1981, courts already have the power to act to avoid publicity or where publicity might substantially risk prejudicing a fair trial. Court can also order a postponement of the publication of any of its proceedings for whatever period it considers necessary. Along with these powers goes the power to prohibit publication of the name (or identification) of anyone connected to the case.

To round off their position the 2002 Home Office letter refers to the cost and number (2%) of the estimated number for false rape allegations:

New Scotland Yard has informed [that] they are unable to supply an estimated cost due to the number of factors involved [i.e. of false rape allegations]. However, researchers have estimated that false complaints account for only 2% of the rape statistics, which is about the same percentage as for many other crimes.

The Dark Side

The dark subject of rape and the much darker subject of false allegations of rape are long overdue an objective re-assessment. It is ironical that in 2002 the graph below was produced showing the rape conviction figures internatioanlly and for a selected number of countries, eg Italy and Greece. The concern then identified as a possible flaw in English accounting for rape statistics remains valid to this day. There is no differnce between what we see in Fig 1 (above) and and the contents of Fig 5, below.

Governments have allegedly undertaken such ‘objective’ reviews but an examination of participants reveals a far from balanced reviewing panel, e.g. Liz Kelly writing on both rape and Domestic Violence.

It might reasonably be assumed that all false allegation cases result in charges of perjury being laid before the complainant who made the false allegation and gave false evidence to the court. However, the reality is very different. The number of perjury cases, as shown in the Table below, circa 200 per annum is far smaller than the number of false allegations made (Fig 6).

In addition it is difficult to initiate a prosecution as the victim of the charge finds that the court is reluctant to act and the police will not act unless the court approves of it. There are, I am sure, very sound technical reasons to explain away this situation but to poor Mr., Joe Public this is how it looks.

Fig 6

In more recent times (2008 – 2010) judges have been more inclined to punish those that make false rape allegations. Sometimes it is probation, a suspended sentence but occasionally it is 2 years for “perverting the course of justice.”

‘Perverting the Course of Justice’ is an indictable Common Law offence but perjury is statute law and an indictable offence under the Perjury Act 1911 (sect 1). [3]

The maximum sentence for perjury is 7 years imprisonment – there is no guidance (i.e. min or max) for perverting the course of justice.

A list of reference cases is given in the Appendix below.

In matters of sexual offending and false allegations of sexual offending there is no political mileage for being radical; for seeking to tackle a decrepit and arcane regime with an enlightened approach. Everyone seems happy with the extraordinary costs of compensation and the concomitant expense of custodial prison sentences, prison staff, and prison building programmes.

The following extract is from the Foreword written by Dennis V. Lindley for Prof Mervyn Stone’s book “Failing to Figure; Whitehall’s costly neglect of statistical reasoning”, [4] itself an indictment of how governments choose to absent themselves from governing:

“Let me conclude this foreword by introducing a personal note. In my early research work, I had made what appeared to be an innocuous assumption and the results, both theoretical and practical, that sprang from it appeared sound. Stone came along and pointed out that the assumption was unsound. He provided an ingenious counter‐example, where the assumption led to transparent nonsense. This upset me greatly and for days I struggled to find a flaw in his work. Reluctantly I came to the conclusion that there was none: he was right and I was wrong. My results needed amendment but it was found that, with the assumption modified to take account of the counter‐example and the principle it involved, the new results were better than the old.”

This paper seeks to question similar cosy assumptions and hopes to unveil to the reader some of the ‘transparent nonsense’ that so bedevils this subject.

Appendix A

Over the years . . . .

Leslie Warren

Leslie Warren spent two years in jail for raping an ex-girlfriend. In March 2003 his conviction was quashed after the court heard that a detective had failed to pass on information about false allegations the woman had made against other men. She later admitted she had lied.

Andrew Bond

In 2002, rape charges against Andrew Bond were dropped after CCTV footage was discovered which showed his accuser fabricating evidence against him.

Austen Donnellan

In 1993, student Austen Donnellan was cleared of date rape after the jury heard that his accuser had been so drunk that she could hardly walk.

Stephen McLaughlin

Worst of all, in 1996 Stephen McLaughlin was accused of rape by a former girlfriend. She later admitted that she had made up the story and was prosecuted. But 18 months later, having never recovered from the shock of the accusation, he drove into a forest and gassed himself to death.

The parliamentary response to these travesties is limited to Charles Clarke MP, replying on behalf of Lord Bassam of the Home Office, that the Gov’t accepts “… the very great distress and discomfort that is often experienced by those wrongly accused or charged with a sex offence ….”.

Appendix B

Dealing with false allegations of rape

Perjury or Perverting ?

Perverting the Course of Justice is a Common Law offence but Perjury is statute law and an indictable offence under the Perjury Act 1911 (sect 1). Perjury carries a 7 year maximum sentence whereas perverting the course of justice has no set tariff.

See CPS Sentencing Manual (April 2010) http://www.cps.gov.uk/legal/s_to_u/sentencing_manual/

See also; http://www.cps.gov.uk/legal/s_to_u/sentencing_manual/perverting_the_course_of_justice/

False allegations of rape.

- R v Merritt [2006] 1 Cr. App. R.(S.) 105 reviewed authorities. Husband accused and held in custody for 9 hours; sentence reduced to 4 months imprisonment.

- R v Fletcher [2006] 2 Cr. App. R. (S.) 24. False allegation led to victim being in police custody for 17 hours and waiting 3 months before being told that no further action would be taken; 2 years imprisonment upheld.

- R v Beeton [2009] 1 Cr.App.R.(S.) 46. Appellant made false allegations of rape against two young men, in respect of one over a period of months and having a profound effect upon him. Sentence reduced to three years imprisonment.

- R v McKenning [2009] 1 Cr.App.R.(S.) 106. False allegation of rape, for which a man was in custody for 27 hours and left in suspense for three months. Every false allegation of rape makes the offence harder to prove and, rightly concerned to avoid the conviction of an innocent man, a jury may find itself unable to be sufficiently sure to return a guilty verdict. Two years imprisonment upheld.

Irony or double standards ?

R. v Hall [2007] 2 Cr.App.R.(S.) 42

The appellant pleaded guilty to conspiracy to pervert the course of justice. He and others indulged over months in very serious and sustained attempts to threaten and intimidate a 15-year-old girl due to give evidence at his trial for a sexual offence against her. Sentence of seven and a half years imprisonment upheld.

Had this person (Hall) not engaged in attempting to pervert the course of justice he might only have had a 5 year or less sentence.

If he can go to jail for 7 years for perverting the course of justice why can’t this be extended to women ?

[1] My apologies for missing data but the manner which the Gov’t presents information is not consistent overtime.

[2] “Cab driver John Worboys jailed for rape and sex attacks” http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/apr/21/john-worboys-cab-driver-jail

[3] See CPS ‘Sentencing Manual’ (April 2010) http://www.cps.gov.uk/legal/s_to_u/sentencing_manual/